When I set out to write this piece, I thought I’d share some jumping off points that have helped me become a more confident transracially adoptive parent. But it grew to include quite a few pieces, so we have decided it’s best broken into two parts. Here you’ll find part 1, and you can jump over to our blog to find part 2. Thanks for being here, putting in the time and energy our kids need from us. –Bear

A friend of mine recently asked me the question, “Who benefits by you staying silent?” I had been telling him about my anxiety over creating a more robust artist presence online for my business—more videos about who I am and why I make what I make—and my hesitation at starting a Patreon account where I’d be able to share more and create community. I told him that almost every time I created a video I felt an intense sense of shame internally: “WHO CARES what I have to say!?” Or “What if people don’t accept me because I’m not enough of one thing or another?” I was sure that the problem was inside me. If not a total moral failing, then at least a personal weakness big enough to stop me from being the person I wanted to be.

This is where we come in—Right this very moment, as primary caregivers, we embody one of the strongest and most impactful forces that will inform how our kids feel about their worth. We are one huge force. We are the ones who educate and frame what the other forces is the world are to our kids: the complexities and intersections of race, adoption, family structure, nationality, religion, wealth, gender, sexuality, age, resource access and institutionalized education (among others) are already shaping how our children think about the world and their place in it. Working toward becoming more conscious and clear-eyed about how we can better move and act amongst these forces outside the status quo* is critical to helping our kids learn to move and act amongst them outside the status quo themselves.

Let’s say our goal is to get our kids to age 40 with clear and confident inner-voices of self-worth, determination and resilience, so that they can trust themselves when they are making important choices, and find joy, excitement and fulfillment in their lives. In this effort, I thought I’d share how I think about our caregiving work.

Becoming a Conscious and Clear-Eyed Adult is a Practice

The work starts with us. Becoming an effective, action-driven, intersectional ally to our kids (and others) is complex, and we need to develop a practice. One analogy that helps motivate me for any skill I deeply want to have, but is very complex and hard to learn is walking, which many of us have the privilege to get to do. How much do we think about walking while we are doing it? Most people with the privilege of healthy legs and bodies don’t think much about walking when they walk. But each of us spent years and years practicing this skill every single day. We fell a lot at the beginning. We cried. We took breaks for short periods of time, but our commitment was strong so the next day we doubled down. Dozens of times a day we got back up and took more steps. By age 4 most of us were pretty good at it. We can’t even remember all that practicing, but we did it. Then we started doing it in different ways. We added jumps and skipping and backwards walking and galloping and cartwheels. It was a complex skill we wouldn’t be experts at for a decade or more.

The following few categories can help us build practices of learning and aligning. These categories intersect in many ways and will help us become capable of walking beside our children with clarity and confidence, centering their experiences and needs, instead of hovering around them and world events in our own anxieties, which centers ourselves.

1. Personal Work

The first work we need to do is internal and personal to only us, and it’s two-fold - recognize your own pain and healing and educate with facts and understand the importance of art

A. Recognize your own pain and healing

“If you aren’t in your body, someone else is. The systems of this world have everything to gain from your disembodiment. Stay near yourself. Remember your body.” - Cole Arthur Riley

We need to be unpacking our own stuff. What holds us back from being the person we truly want to be? If we want it for our kids, we need to want it for ourselves. In what ways do we not advocate for ourselves because we’re not sure what to say? In what ways do we sacrifice our important needs for others or because we learned we shouldn’t have those kinds of needs? Get a therapist. Write things down, do some digging, start with honesty. You will learn as you practice. You will know the way forward as you move forward. It is important that our kids see us repairing our own hearts and minds, protecting our own dignity and joy and taking accountability for the mistakes we’ve made and harms we’ve caused. It is important that our kids see that we, ourselves, care about living full, purposeful lives not hidden under rocks of shame, guilt, fear or worse, entitlement and flowery platitudes. This is hard life-long work, and it requires a growth mindset where facts and art can work in concert.

B. Educate with facts and understand the importance of art

Most of us simply need to know more about why racism exists and how it impacts politics, communities and our wellness. Here are some leads on learning more about race and racism in the United States: Have you read Stamped From the Beginning by Ibram X. Kendi? Have you read works by Nikole Hannah-Jones, Ta-Nehisi Coates, June Jordan and James Baldwin? Do you know the works of Cole Arthur Riley, Prentis Hemphill, Sonya Renee Taylor, Shannon Gibney, Kwame Alexander, Romare Bearden, Augusta Savage? Racism doesn’t exist in a vacuum away from other negative forces like patriarchy, queer-phobia, ableism and class, which all intersect in works by these authors and artists, as they always do. Study the subject of race and racism within the larger context in which it was created and exists. We need to understand a history that doesn’t erase the political, social and economic policies and structures that created the concept of race and White supremacy** in order to use some people deemed less-than to build an empire guilt-free, and the long history of implications that got us to where we are today.

It is important for our kids to see that we are working to untangle the forces of White supremacy that live inside us, in our communities and in the wider world. It is important that our children see us trusting the experiences of people who are different from us because we personally care–not just because we want it for them. It’s important that our children see us truly loving and protecting other people who look like them.

[Growth Mindset can help us with this. When you believe you can always learn more, and you can be with the vulnerability of necessary failure along the way, you will progress. We don’t know everything already. We need to be willing to read and listen more than we talk, let what we learn change our perspectives, beliefs and then our behaviors. Growth mindset involves giving ourselves compassion enough to use phrases like this: “I’m not sure, let me learn more!” and “I messed up, how can I repair, I forgive myself, how can I do better next time.”]

2. Allyship: Our Own Beliefs and Priorities In Action

There is often a distinction between the beliefs and priorities we have because we just really care about them in a tangible way and likely always have, and the beliefs and priorities we have because we know we should have them for our kids (or because that is what “good” people do). The problem with caring about anti-racism work only because our kids would benefit from it is that a.) We will do less work because we aren’t immersed in the importance of it ourselves, and b.) Our kids can see surface-level engagement vs. soul-level engagement, and they will carry that knowing with them.

Audre Lorde said that our children are in our lives to hold us accountable. In other words, being motivated to do this work for our specific kids is a great way to start, but if we are only taking action for our specific kids, we are not fully embodying what it means to be an ally—to care at a level that is deeply personal enough that we would take action even without our kids present, making an impact in the greater community that our kids are a part of. Our care for people with identities different than our own shows up as care for our children.

Action and sacrifice is what true allyship is. Not social media posts and flags on the porch and t-shirts. Those are visibility—also important, but contain no substance without the action to back it up. We have to want to work toward an alignment between what we’re willing to take action on because we care about it personally regardless of our kids. It is important that our children see us framing the possibilities of human experience as rooted in truth, integrity, accountability and community care.

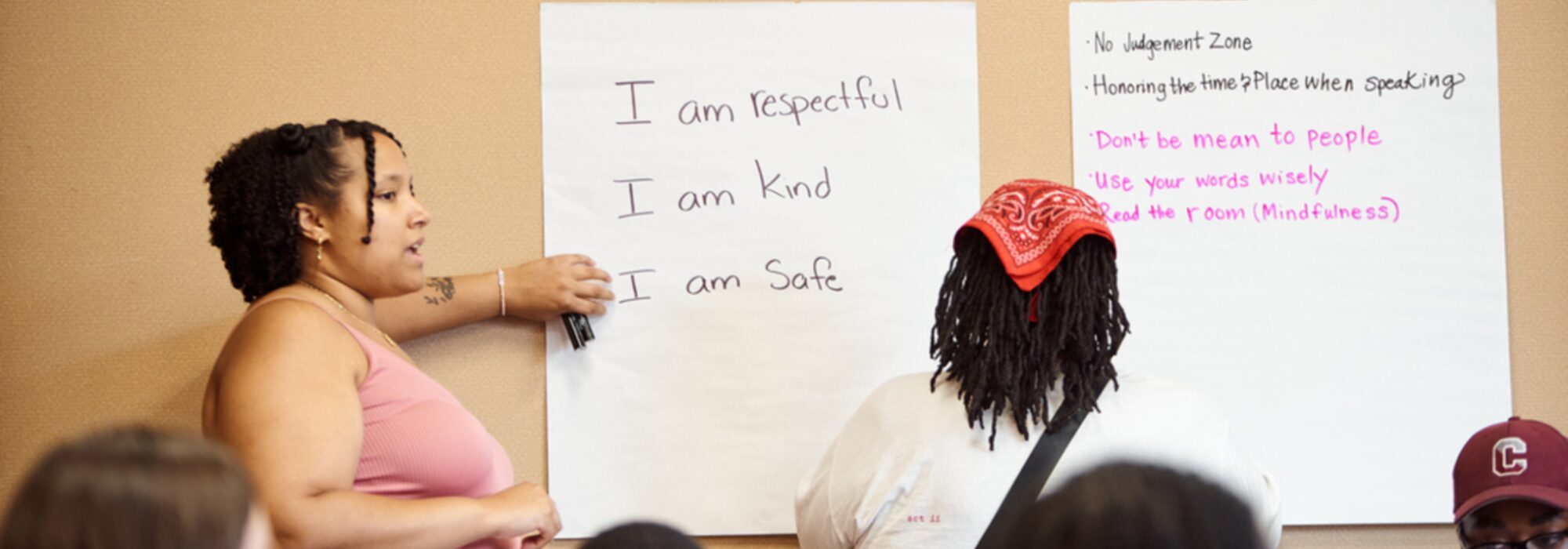

3. Our Parenting at Home

How we show up for our kids at home is different than in public and with family, but it all has to contain the same thread: We are the upholders of our children’s dignity. How often do we interrupt a person, a system, a curriculum, a movie, in order to stop harm or to validate and contextualize the harm being experienced for our children? How can we have conversations about this with our kids that feels empowering, which don’t offload our anxieties onto them? It is important to find ways to celebrate joy and pride with our children that aren’t in the context of whiteness, and the fastest way to do this is to care yourself, personally, in your free time. Transracial Journeys has conversation card packs that can open up a variety of conversations at home. The practices in No. 1 & No. 2 will help us embody clear values in our actions that our kids will notice (even if they never mention it or engage with you about it).

*When I use the term status quo, I’m referring to the project of White Supremacy, which inherently contains the intersections of racialized human value as well as how narrow and harmful concepts of gender, sexuality, nationality, class and ability are used to uphold harmful power structures. All of these forces are tangled up in each other, referring back to each other constantly like a pro sports team— this entanglement is called intersectionality.

**White supremacy is the belief that the white race is inherently superior to other races and that white people should have control over people of other races. It also refers to the social, economic, and political systems that collectively enable white people to maintain power over people of other races (merriam webster).This term is often used in the context of institutional and political legacies and continued use of practices that support maintaining wealth and power for White people over non-white people. In other words, one does not have to believe personally that White people are superior to other races to be participating in habits, behaviors, rules, norms, laws and systems that were created to explicitly keep White supremacy running, but that haven’t been updated fully yet.

This is the end of part 1 of this article. Part two will include: Parenting Outside the Home, Connecting to Extended Family Through Adoption, Room for Grief and Hope at the Same Time and Interrupting. You can find part 2 at Moving Through Life with Clarity and Confidence (Part 2)

Bear Howe is a white adoptive TRJ parent.